Extraction of natural resources is a high-risk sector and it often takes place in countries where human rights violations are common and governance structures are weak. It is important that the companies are aware of this and conduct thorough risk assessments. The duty of states and the responsibility of companies when it comes to respecting human rights is outlined in the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights.

The extraction of natural resources is characterised by many risks in terms of negative environmental impacts and human rights abuses. Companies are responsible for respecting human rights in all their business activities and have opportunities to contribute to positive change. However, this is associated with several challenges. Many companies are unaware of how their business activities impact human rights and the environment because supply chains in the extractive sector tend to be long and complex, with extensive geographical spread. There is often a lack of knowledge about where raw materials are extracted, where they are refined and treated, or where the final assembly takes place. Raw materials such as minerals, metals, and oil are also often purchased on commodity exchanges, where raw materials from different mines, smelters or other sources are mixed. This makes traceability virtually non-existent.

The extraction of raw materials often takes place in countries and regions where states have failed to protect human rights, or where states themselves are guilty of abuses. In these countries, poverty, weak democratic institutions, widespread corruption, and legal safeguards that are insufficient or are not enforced – factors that typically increase the risk of people being negatively impacted by business operations. Despite challenging conditions and flawed traceability, companies have a clear responsibility to respect human rights throughout their supply chains, regardless of where they operate in the world. This is outlined in the UN’s guiding principles on business and human rights.

UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights

To clarify companies’ human rights responsibilities, the UN has developed the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGP), that define what is expected of states and companies respectively, and how businesses should, in practical terms, work to respect human rights throughout their supply chains. The UN Human Rights Council adopted the principles in 2011. In addition to the UN guiding principles, there are several internationally recognised standards and guidelines that encourage companies to take greater social responsibility, all of which have integrated the UN principles. Therefore, the UN guiding principles are to be considered as a norm and the starting point for corporate responsibility in terms of human rights in general, and which there is consensus around. The UN also encourages member states to develop national action plans to meet UNGP guidelines. Such action plans have been developed by several countries, including in Sweden in 2015.

| Tip!

FAQ about UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights |

Representatives from Swedish energy company Vattenfall visit villages affected by coal mining in Colombia in 2017. Photo: Carlos Cardenas, Forum Syd.

The UN guiding principles on business and human rights are built on three core pillars: Protect, Respect, Remedy. The first pillar asserts that states have an overarching responsibility to protect their citizens from third parties, for example, a company, from impacting human rights negatively. This is achieved by, for instance, ensuring that laws are in place and are correctly implemented. Pillar two states that businesses have a responsibility to respect human rights across their operations, including all supply chains and business relationships, regardless of a company’s size, structure or sector. Companies are responsible always and around the world, even when production is conducted in states with weak democratic institutions and control mechanisms, which fail to enforce existing legislation and conventions and thereby do not protect citizens’ human rights. Special care must be taken of vulnerable groups, for example, children, women, migrant workers, and indigenous people. The third pillar relates to states and businesses having a responsibility to provide access to remedy that allows those who feel that their human rights have been affected negatively by a company’s actions to raise their grievances and obtain compensation when necessary, for example through financial payments.

Human Rights Due Diligence

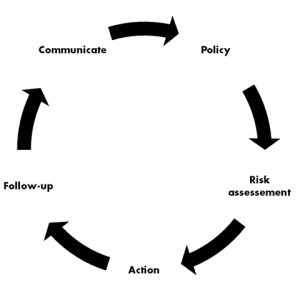

To enable businesses to identify, prevent, mitigate, redress, and evaluate how they manage their negative impact on human rights, they need to conduct a so-called Human Rights Due Diligence. This is a multi-step, on-going process that, in brief, requires companies:

To enable businesses to identify, prevent, mitigate, redress, and evaluate how they manage their negative impact on human rights, they need to conduct a so-called Human Rights Due Diligence. This is a multi-step, on-going process that, in brief, requires companies:

- To have a process in place to identify and assess its negative impact, or risk of negative impact, on human rights. This should be based on meaningful consultation with stakeholders, i.e. someone who is, or potentially will be, impacted by the company’s operations, or in some way has an interest in or influence over a company’s operations.

- To undertake relevant measures to address, counteract and prevent real, or risk of, negative impact.

- To follow-up and assess the effectiveness of the measures in practice.

- To openly communicate how the company operates according to the “know & show” principle, and to be accessible for stakeholders.

Furthermore, the company should have a policy commitment that includes all human rights, for example, a code of conduct, adopted at the highest levels and communicated throughout the company, as well as to customers, suppliers, and other relevant parties. In those cases where the company identifies a large number of risks and/or cases of negative impact, the company must prioritise the most extensive and severe risks and/or cases.

Discussion point 1:Does the company have a policy that includes all human rights? Who is responsible for it and who has approved it? Is everyone in the company aware of the policy and how it is used? Discussion point 2:What risks has the company identified? Discussion point 3:How well has the company communicated to the public (for example through sustainability reports) about its own impact and its risks? Tip!Read more in the UN guiding principles about what the Human Rights Due Diligence process means in every step (page 18). Shift has published an guiding report on how businesses can identify and prioritise risks in the supply chains. The OECD has infographics on the Due Diligence steps that have been adapted for the mineral extraction sector, both upstream and downstream in the supply chain. The infographics are based on the OECD’s Due Diligence Guide for mineral extraction. The Somo Institute has produced a guide for organisations wanting to investigate company practices based on the UNGP. ESCR-Net and the Business & Human Rights Resource Centre has produced a checklist for local communities or other organisations to document businesses’ negative impacts. A form can also be submitted for publication by the Business & Human Rights Resource Centre. Exercise:Conduct a risk mapping of the company’s supply chain. Relevant questions:

|

Stakeholder involvement

A company typically has a large number of stakeholders. A fundamental element of the entire Human Rights Due Diligence process is to involve those whom the company can potentially or genuinely influence. Local communities are extremely important stakeholders in the extractive sector because they are especially vulnerable when, for example, mines are sunk. Workers, suppliers, local authorities, trade unions, and civil society are all examples of stakeholders. Involving these groups is necessary to gain insights into the risks and actual impacts that exist, but also how issues can be resolved and addressed; and whether a need for compensation exists. It is important that stakeholders are involved in meaningful ways, and that an exchange of information is established on an ongoing basis. By gathering knowledge from stakeholders about local conditions, and enabling honest dialogue with local communities, businesses can also save large amounts of money, and avoid their operations being exposed to protests or future strike action. One of the most common forms of stakeholder dialogue for companies is collective negotiation and collective agreement, which is a way to ensure that the dialogue is meaningful for the workers and addresses aspects such as salary and working conditions.

Exercise:Brainstorm and draw up a stakeholder map for your own company. What stakeholders do you have inside and outside your company? Who of these can be impacted negatively by your operations? Which stakeholders are the most vulnerable? Tip! The OECD has produced guidelines for meaningful stakeholder involvement in the extraction sector. The Danish Institute for Human Rights has developed guidelines for how stakeholders can be involved in the Due Diligence process. |

The Altropico organisation works to protect human rights and natural areas in Ecuador, a country where mining affects nearby villages and threatens livelihoods. Photo: Luis Manolo Yela Casanova, Altropico

Other overarching standards and guidelines

There are other guidelines and standards that have been developed around corporate responsibility that have integrated the UN guiding principles on business and human rights.

The OECD has produced voluntary guidelines on corporate responsibility for multinational companies. These are supported by OECD member states and other states that have opted to comply with the guidelines. They should be considered recommendations from states and what they expect of companies, and includes human rights, working and employment conditions – and relationships between labour market actors, the environment, bribery, corruption, blackmail, competition, taxation, and consumer interests. The OECD has also developed a set of guidelines specifically for mineral extraction.

| Tip! TUAC, LO, TCO, and SACO have produced a handbook on the OECD’s guidelines for trade unions. |

The UN’s Global Compact is currently the world’s largest corporate responsibility initiative, with some 1,300 signatory companies and organisations in 170 countries. Every company that joins the initiative agrees to support the Global Compact’s ten principles that cover areas such as human rights, the environment, employment rights and anti-corruption. Companies are required to publish reports on how they work to comply with the principles of the initiative, and what improvements have been made.

ISO 26000 is a set of guidelines for social and corporate responsibility. It defines social responsibilities, and what organisations can do to work towards sustainable development. It is aimed at the private and public sectors and includes guidelines for how work with social responsibility should be conducted. The standard is based on seven basic principles and seven key issues. The key issues include organisational governance, human rights, working conditions, the environment, responsible business practice, consumer issues, and local societal development. Unlike other ISO standards, it cannot be certified, as is the case with, for example, ISO 14001, since it does not include any specific requirements that can be complied with.