RIGHTS

Photo: Javier De la Cuadra

Armed conflict

The extraction of oil and minerals can be used as efficient economic means to fuel armed conflict. Four minerals, more than any others, have played decisive roles in financing one of the world’s longest and bloodiest conflicts – a conflict that continues to rage between different armed groups in the northeast of the Democratic Republic of Congo (Congo Kinshasa). The UN has therefore assigned these minerals – tin, tantalum, tungsten, and gold – a special status as “conflict minerals”. The four are included in components for electronic devices, and are used in the manufacture of smartphones, computers, and vehicles. Many experts argue that more minerals should be classed as conflict minerals because armed groups in different parts of the world finance their operations from mining.

Some examples

- Swedish prosecutors are currently conducting a criminal investigation into Lundin Petroleum. Lundin’s chairman and CEO are suspected of involvement in serious crimes against international law in South Sudan. The crimes are believed to have been committed during the brutal civil war when the company was prospecting for oil on the country. The presence of international oil companies increased the strategic significance of the oil fields and contributed to the deaths of thousands of people and forced tens of thousands of people to flee. Lundin Petroleum state themselves that they acted for peace in the country.

- In Mexico, cartels increasingly finance themselves through informal gold mining. Cartels conduct violent and systematic extortion of local communities and are responsible for human trafficking and sexual violence.

- Taliban groups and local militias earn an estimated USD 50 million a year by controlling mines in northern Afghanistan, (including lapis lazuli, which is used in jewellery). The country is rich in minerals and precious stones and much of the small-scale mining in Afghanistan is conducted illegally.

Illegal logging often occurs in regions where armed conflict is rife, such as on the border between Laos and Cambodia. Revenue from logging is linked to the arms trade in the region.

Land rights and forced relocation

Mining operations typically require large amounts of land, making land disputes one of the sector’s most pressing challenges. In countries characterised by widespread corruption, administrative structures related to the granting of concession rights to mining companies are often shadowy. Many governments are accused of enabling land theft. In many parts of Africa south of the Sahara, local populations lack formal rights to land on which they have lived for generations. This makes them vulnerable to companies applying for mining licences.

In many areas forced relocations of villagers or entire villages in the way of the expansion of mining operations or other extraction projects. Forced relocations are often characterised by extreme violence, poor compensation, relocation to new areas with poor housing and limited opportunities. Forced relocations linked to mining and oil extraction occur in many cases indirectly, for example as the result of environmental destruction and water shortages caused by extraction activities.

Some examples

- The construction of a new mine in a remote area of north western Zambia required the relocation of 4,000 people. According to Canadian mining company, the relocation went smoothly. However, a survey conducted by Swedwatch in 2018 revealed that villagers faced much longer journeys to a market making it harder for them to sell their cereals and vegetables. Furthermore, they no longer had access to forests to pick mushrooms and other forest products. After the relocation, it was harder for the villagers to support themselves and their families.

- The Mtwara-Dar es Salaam natural gas pipeline passes through 113 villages in Tanzania and was completed in 2015 after several years of violent protests. Relocated families accuse companies and the government of breaking off dialogue with affected households, and of failing to respect ancestral burial grounds that form a key element of their culture.

- According to Amnesty International, mining activities in India led by state-owned mining company Coal India has resulted in the relocation of some 87,000 people in the past 40 years. A large proportion of those who have been moved are Adivasi, a people with strong bonds to their land and forests. The affected Adivasi groups report that they have been excluded from decision making related to the land that, according to tradition, belongs to them. Many have waited for decades for promised compensation.

Indigenous peoples’ rights

Illegal logging and extraction of minerals, oil, and natural gas frequently threatens indigenous people and their traditional ways of life. Many mining companies actively seek to access isolated and unexploited areas that are rich in natural resources. Such areas often overlap with indigenous peoples’ lands. The UN declaration on indigenous peoples’ rights states that indigenous people cannot be forcibly removed from their land. No relocation is permitted unless those affected give their consent in advance and based on all available information, according to the principles of Free Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC). These principles are also included in the International Labour Organization (ILO) convention 169, which many countries have ratified. Despite this, governments in some countries ignore these rights and grant concessions to extractive companies, often after dubious processes and without prior consent of affected indigenous people.

Some examples

- Illegal logging in the Amazon in Brazil is extensive and exposes indigenous people to violence and confrontation. Many indigenous groups have been forced to flee and some face extermination following the loss of their homelands to illegal logging. For example, the Karipuna in northern Brazil, where more than 10,000 hectares of their territory has been destroyed according to Greenpeace. Amnesty International reports that leaders of the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau and Arara are subject to death threats when they defend their traditional land from loggers.

- The Marlin gold mine in Guatemala, a vast, open pit mine, has attracted criticism for its impact on the rights of indigenous people for more than two decades. The UN has highlighted flawed and dubious consultation with affected indigenous groups, severe water pollution and depletion of water sources, and extreme violence at the hands of security staff employed by the mining company. Local people report how their culture is dying out as outside mining personnel move in and contribute to social problems such as prostitution and alcoholism.

- In the Philippines, indigenous leaders are increasingly being threatened and are the victims of violence when they protest against mining or other extractive projects that affect them. A leader of the Ifugao Peasant Movement, who had protested against the construction of a dam, was shot dead in 2018 and a leader of the Lumad was murdered when he led protests against the extraction of minerals on their traditional lands. The Lumad live on land rich in natural resources and valuable forest, which has attracted large-scale mining and forestry companies.

- In Peru, the Camisea natural gas project has had a major impact on different indigenous groups. For example, new, and in some cases fatal, illnesses are spread among groups that are highly vulnerable to new bacteria because they live in such isolated areas. The Camisea project has provoked strong criticism over its planned expansion due to fears that this could result in indigenous groups dying out.

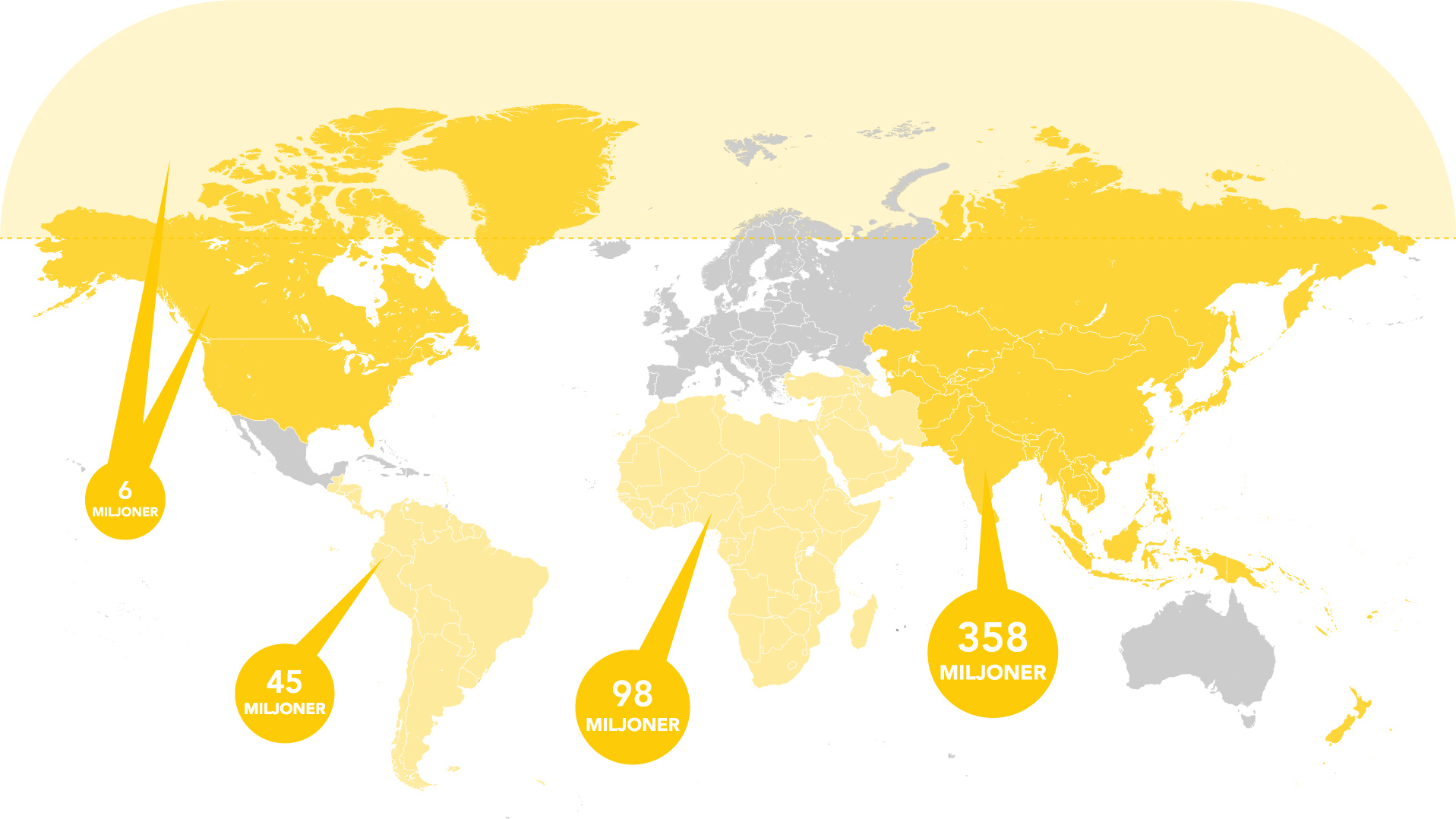

Indigenous people around the world

Indigenous people make up about five per cent of the world’s total population and number around 370 million across some 90 countries. Of these, 60 million people are almost entirely dependent on forests for their livelihoods. Their traditional lands make up almost 20 per cent of the world’s total land area. Source: World Bank

Violence and security

Threats and violence against those who defend their basic rights are escalating in many places around the world. In many cases, there are direct or indirect linkages to corporate activity. Sectors that are especially dangerous for human rights defenders include agribusiness, mining, oil, gas and large-scale dam building. Local- and indigenous populations who defend their rights to land, the environment and natural resources are especially vulnerable. People active in trade unions and those who are standing up for rights at workplaces is another particularly vulnerable group. Brazil, Mexico, Colombia, Honduras, Guatemala, Philippines and South Africa are some of the countries that have seen most attacks on those who defend their rights in the face of corporate activity. In some cases, companies have been involved when states have introduced tougher legislation to limit civil society. In many areas, where the mining sector is important to a country’s economy, states have defended companies against accusations of human rights abuses.

Extractive industries are responsible for considerable investment aimed at recovering precious raw materials. Many extraction activities therefore involve private security forces, and sometimes require companies to enter into special agreements with police and the military to protect sites. Tension caused by the increased presence of weapons and security personnel, extreme violence against local populations, and unlawful arrests of people resisting the presence of companies are common in many parts of the world, primarily in Latin America, Africa and Asia.

Some examples

- In Cambodia, illegal mining of sand has become a major industry, involving high degrees of corruption. According to local environmental organisations, sand mining results in the collapse of protective sandbars and that important ecosystems, for example for shrimp and crab, are destroyed. In 2017, two environmental activists were arrested for filming boats suspected of transporting illegal sand. The pair were given a one-year prison term, although were released earlier.

- Incidents of murder, rape, torture, and violence against the local population have been documented for many years in and around the Grasberg gold and copper mine on the island of Papua, Indonesia. Private security forces hired by mining company Freeport McMoRan, local police and military forces are responsible for the abuse. The company paid millions of dollars to local police and the military for many years, in suspicious circumstances. In 2018, the Indonesian state took majority ownership of the mine. It is unclear how the state will manage the long-running conflict between the local population, the mine and the security companies, nor the extensive damage the mine has caused.

- In many parts of the world it has become increasingly dangerous to defend human rights and the environment from extractive activities and large-scale agriculture. In 2019, record numbers of environment and human rights defenders were killed all over the world, (304 persons in 31 countries). The five most dangerous countries were Colombia, the Philippines, Honduras, Mexico and Brazil. Read more in Forum Syd’s report Defending their Rights, Risking their Lives.

- The Philippines is one of the deadliest countries in the world for human rights defenders with 43 murders reported in 2019. Violence is especially directed towards those who defend land rights, and in many cases, linkages exist between mining or the exploitation of natural resources. Farmers have been murdered after protesting against large-scale plantations and a lawyer who represented small holders’ rights was shot dead. Perpetrators often go unpunished and the murders are seldom investigated.

Jimmy Saypan, a leader of the indigenous people Lumad in the Philippines, who was murdered after leading protests against the extraction of minerals in their traditional areas. Photo: Center for Environmental Concerns.