Illegal logging and extraction of minerals, oil, and natural gas frequently threatens indigenous people and their traditional ways of life. Many mining companies actively seek to access isolated and unexploited areas that are rich in natural resources. Such areas often overlap with indigenous peoples’ lands. The UN declaration on indigenous peoples’ rights states that indigenous people cannot be forcibly removed from their land. No relocation is permitted unless those affected give their consent in advance and based on all available information, according to the principles of Free Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC). These principles are also included in the International Labour Organization (ILO) convention 169, which many countries have ratified. Despite this, governments in some countries ignore these rights and grant concessions to extractive companies, often after dubious processes and without prior consent of affected indigenous people.

Some examples

- Illegal logging in the Amazon in Brazil is extensive and exposes indigenous people to violence and confrontation. Many indigenous groups have been forced to flee and some face extermination following the loss of their homelands to illegal logging. For example, the Karipuna in northern Brazil, where more than 10,000 hectares of their territory has been destroyed according to Greenpeace. Amnesty International reports that leaders of the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau and Arara are subject to death threats when they defend their traditional land from loggers.

- The Marlin gold mine in Guatemala, a vast, open pit mine, has attracted criticism for its impact on the rights of indigenous people for more than two decades. The UN has highlighted flawed and dubious consultation with affected indigenous groups, severe water pollution and depletion of water sources, and extreme violence at the hands of security staff employed by the mining company. Local people report how their culture is dying out as outside mining personnel move in and contribute to social problems such as prostitution and alcoholism.

- In the Philippines, indigenous leaders are increasingly being threatened and are the victims of violence when they protest against mining or other extractive projects that affect them. A leader of the Ifugao Peasant Movement, who had protested against the construction of a dam, was shot dead in 2018 and a leader of the Lumad was murdered when he led protests against the extraction of minerals on their traditional lands. The Lumad live on land rich in natural resources and valuable forest, which has attracted large-scale mining and forestry companies.

- In Peru, the Camisea natural gas project has had a major impact on different indigenous groups. For example, new, and in some cases fatal, illnesses are spread among groups that are highly vulnerable to new bacteria because they live in such isolated areas. The Camisea project has provoked strong criticism over its planned expansion due to fears that this could result in indigenous groups dying out.

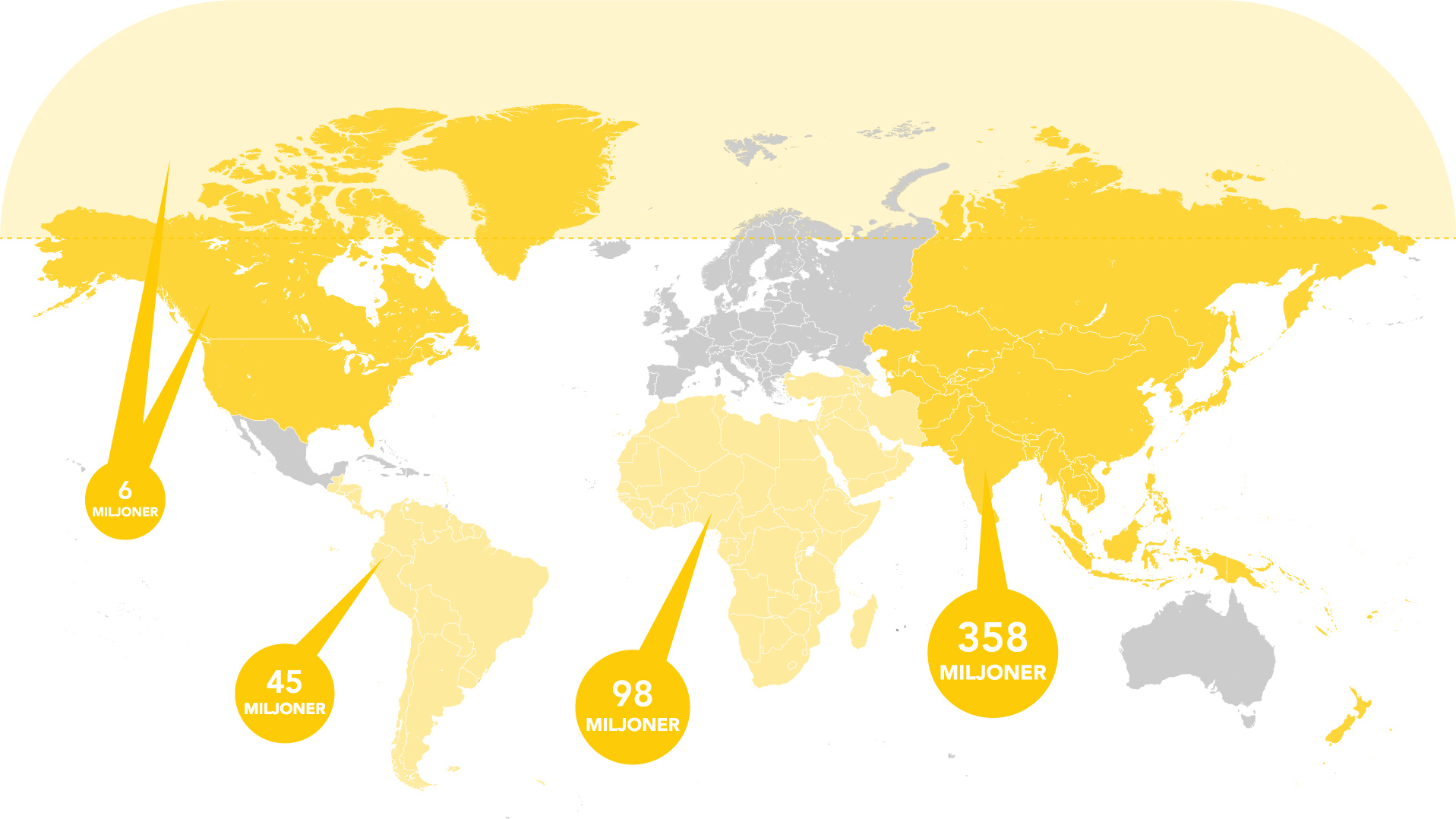

Indigenous people around the world

Indigenous people make up about five per cent of the world’s total population and number around 370 million across some 90 countries. Of these, 60 million people are almost entirely dependent on forests for their livelihoods. Their traditional lands make up almost 20 per cent of the world’s total land area. Source: World Bank