SOCIAL RISKS

Photo: Swedwatch

Working conditions

Many mines and oil installations have been modernised and have become safe workplaces, where machines now perform the most hazardous tasks. In many countries, however, mines remain the deadliest type of workplace, where collapses, landslides, drowning, and pulmonary illnesses claim thousands of miners’ lives every year. In many cases, informal/small-scale mines represent the most dangerous form of mining because protection and safety equipment are usually non-existent. Trade unions are seldom represented at small-scale and informal mines. Dialogue with workers associations here is often non-existent, which even further increases the vulnerability of the miners and their lack of influence over their working conditions.

The extractive industries are overwhelmingly male-dominated workplaces. Women who work in mining and extraction can be particularly vulnerable, especially for sexual abuse.

Miners in front of the entrance to a cassiterite mine in Congo Kinshasa. There is a severe risk of collapse at these types of mine, which typically have narrow and deep shafts. Photo: Jeppe Schilder.

Some examples

- In January 2019, a tailings dam collapsed at an iron ore mine in Brumadinho in south east Brazil causing the deaths of more than 250 people. A vast river of mud containing toxic mining waste flooded the area and drowned people, buildings, roads and bridges. It was the deadliest mining accident in Brazil’s history. The Brazilian company Vale, which operates the mine, is the world’s largest producer of iron ore. Internal documents show that Vale knew that the dam was flawed. In 2015, one of the company’s tailings dams at another mine in the same state collapsed resulting in the deaths of 19 people.

- In February 2019, a landslide hit an illegal gold mine on the island of Sulawesi in Indonesia. Wooden structures in the mine collapsed due to loose earth and the large number of mine shafts, which resulted in many people being buried in debris. At least eight people died, and many other miners were reported missing. The area is inaccessible and located in steep terrain, which complicated rescue efforts. Unofficial, unlicensed mines are common in Indonesia, and safety standards are often poor.

- In March 2019, a leaking oil pipeline caused a major explosion in the Niger Delta in southern Nigeria. More than 50 people went missing after the explosion and the accident caused widespread oil spills throughout the delta. The Niger Delta is heavily polluted by repeated oil spills. According to Nigerian oil companies, pipelines are destroyed, often with the aim of stealing oil or for reasons of sabotage. Fatal accidents caused by leaking oil pipelines are common in Nigeria, which is Africa’s largest oil producer. According to Amnesty, the large international oil companies fail to take sufficient steps to prevent oil spills or sabotage, and they react too slowly when pipelines are leaking.

Forced labour

Forced labour, also referred to as modern slavery, frequently occurs in regions with limited insight from the outside world. Forced labour includes people who are not free to leave their work without the risk of reprisal; people who have entered into employment under uninformed circumstances, people who automatically are becoming trapped in debt traps or who are not paid a salary as promised. As mines and forests are often isolated from larger communities, the extractive industries account for a considerable proportion of the total 20 to 45 million people that are currently trapped in forced labour.

Some examples

- North Korea has the largest number of people working in forced labour. According to the Global Slavery Index, 2.6 million North Koreans – one in ten – were working as forced labour in 2018. In most cases, it is the state that forces people to work in slave-like conditions. Forced labour exists in mining, for example in extraction of coal and iron ore.

- Forced labour occurs in diamond mines in Angola. For example, migrants from Congo Kinshasa work in mines in conditions close to forced labour. Women and children are trafficked for prostitution in mining areas. Criminal networks transport Congolese girls as young as 12 to Angola as forced labour and for prostitution.

- The Central African Republic comes fourth in the Global Slavery Index of countries where modern slavery is most prevalent. People trafficking, primarily children, for forced labour and sexual exploitation is widespread. Mining, for example of diamonds, and logging are sectors where forced labour occurs.

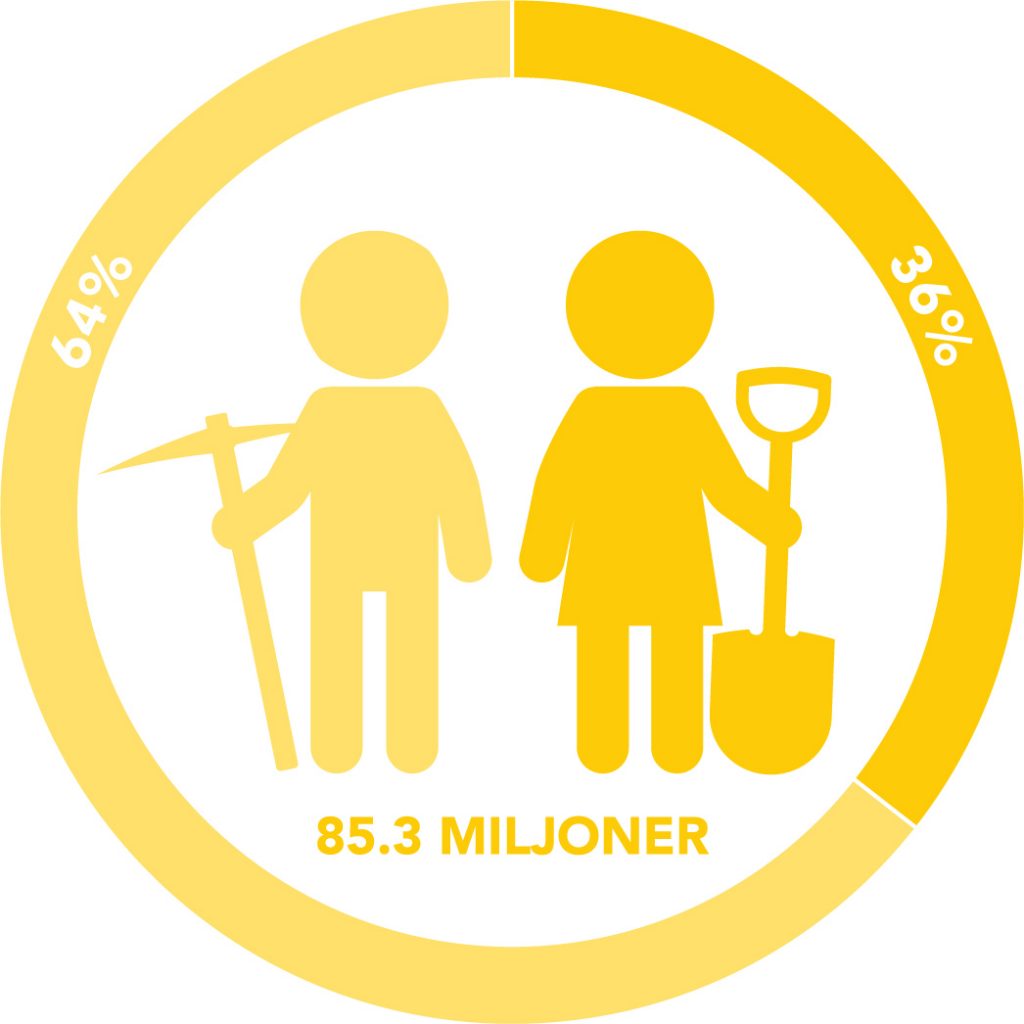

Child labour

A significant proportion of the 168 million children who, according to the International Labour Organisation (ILO), work globally, are found in the extractive industries, primarily in informal mines. The use of toxic chemicals such as mercury, (used to separate gold), is common in informal mines. Children are especially vulnerable to such chemicals, which can inhibit their development. Mercury attacks the central nervous system and can cause brain damage and death. Under international principles, work performed by children below 18 years in mines falls into the category of the worst forms of child labour. Child labour in logging is widespread in certain parts of Asia and occurs to a certain extent in oil extraction.

Child labour in hazardous working environments

Some examples

- Amnesty International reports that tens of thousands of children mine minerals such as cobalt, tungsten, and gold in Congo Kinshasa for up to 12 hours a day. Some children work down in the mine shafts with miners, others sift through mine waste or sort and clean minerals. Many children report being the victims of violence and extortion at the hands of guards and buyers.

- More than 6,000 children are estimated to work in tin extraction in Indonesia. Working conditions are harsh with the risk of landslides and falls from high altitudes. Many children are forced to work standing in water, where they become cold and risk drowning.

- More than 58,000 children in Vietnam aged between five and 17 are involved in the production of timber. Close to 90 per cent of them work in conditions that according to national law are classed as “dangerous”. Child labour also occurs in Cambodia and Myanmar in teak felling. According to an ILO report released in June 2019, there are more than one million child labourers in Myanmar. Some 600,000 children work in hazardous conditions with severe risks to their health and safety.

- In the Philippines, thousands of children dive in underwater mines to recover gold. Drowning, pain, fever, and spasms are rife. Many children spend several hours in water contaminated with mercury.

Health problems

In many developing countries, large-scale mining operations are often linked to a variety of chronic negative health effects for those working in mines and among local populations. Mining tends to involve a variety of chemicals, (such as mercury and arsenic), and large amounts of water, which can affect local populations’ access to clean water. Chemical spills and water shortages caused by mining, and pollution from oil extraction can lead to poorer harvests and reduced fishing opportunities. This, in turn, can result in severe consequences for the local populations’ nutritional intake and livelihoods. Reports from mining regions in Asia, Africa, and South America illustrate how the extractive industries’ emissions of toxic chemicals in watercourses have caused cancer, renal failure, silicosis, skin conditions, birth defects, infertility, and a number of other diseases.

Some examples

- In Nigeria, decades of pollution from oil pipelines have turned the Niger Delta into one of the world’s most polluted areas. Villages are located next to lakes of oil, affecting people’s health. The extraction of oil releases natural gas, which in the Niger Delta is often burnt off directly into the atmosphere, (so-called flaring). Impurities released by flaring can cause cancer, lung and respiratory system damage. It is estimated that two million people live within four kilometres of a gas flare.

- The mining industry uses sulphuric acid for the extraction and treatment of copper. During these chemical processes, an acidic mist is created that is harmful to the skin, eyes, and lungs. It also affects crops and contaminates water. In Zambia, one of the world’s largest copper producers, thousands of people suffer health problems due to pollution caused by its copper mines. This is particularly the case for the huge Mopani mine, owned by mining group Glencore, which has become infamous for its environmental and health impacts. Several multi-national mining companies active in Zambia have been sued for their lack of action on these issues.

- Dust from coal mines affects nearby communities, and can lead to, among other things, lung disease in primarily miners. Workers are also exposed to silica dust, which can lead to silicosis, cancer, tuberculosis, and other illnesses. These in turn can result in disabilities and premature death. More than one million miners have been exposed to silica dust. Many years of silica dust emissions from Latin America’s largest open-surface mine, the Cerrejón coal mine in Colombia, is estimated to affect the health of 13,000 people. People who live near the mine are affected by rashes, stomach complaints, eye infections, and breathing difficulties.

Coal dust from Colombia’s largest coal mine, Cerrejón, affects surrounding communities.

Sexual exploitation

Mining operations, regardless of whether they are formal or informal, tend to be male-dominated workplaces. As large numbers of men leave their homes and move to new areas, they impact host communities.

In many places, tensions are created that lead to violence, increased alcoholism, and sexual violence, above all towards women and girls. It is also common for women and girls to fall into in prostitution, and HIV/Aids tends to be over-represented in areas close to mining activity. Security personnel who are employed at mines and oil installations are often responsible for brutal sexual abuse of women and girls. The true number of victims of sexual violence is huge.

Some examples

- In Congo Kinshasa, rape and other forms of sexual violence are commonly used weapons in conflicts related to the control of mining operations and the vast natural resources in the country. This sort of sexual violence is particularly prevalent at illegal mining sites. Growing numbers of young girls are victims of sexual violence and pregnancies among the young are common. Female victims are often unable to return home due to shame and the stigma associated with sexual violence.

- The UN reported a marked increase in mass rape and sexual violence in South Sudan in 2018. Violence against women and young girls was believed to be especially brutal. The struggle for oil resources between government troops and rebel groups fuel violence and the UN has warned international oil companies over their potential complicity in human rights abuses related to the extraction of oil.

- In Marange in eastern Zimbabwe, diamond mining has brought with it conflict, forced labour and sexual violence. Local populations have been excluded from the profits of diamond mining and have instead been exposed to widespread suffering.

Sexual abuse is common at mineral extraction sites in Congo Kinshasa. Photo: Roland Brockman/MISEREOR